You might’ve heard it called a million different things like “B-F-R”,” occlusion”, “tourniquet training”, etc. but it’s all based on a simple premise and these terms will be used interchangeably throughout this article. Blood Flow Restriction training is the process of taking some mechanism like a cuff or wrap or anything and creating a tourniquet at the proximal joint (shoulder or hip) so that the arms or legs receive less blood flow while performing exercise. The amount of blood flow restricted in clinical settings will be set exactly at the point of diastolic occlusion. This means that during diastole or when the heart is filling with blood after a contraction, no blood flow will pass through the occluded limbs. In the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle however, when the heart contracts, the pressure will allow for blood to circulate in the occluded limb. This results in a pooling effect where blood accumulates in the limb while occluded since the pressure in the veins is less than the arteries. For the “Bro’s” implementing this in the gym, a general 7 out of 10 tightness for the shoulders and an 8 out of 10 tightness for the legs on a scale of perceived discomfort/exertion is recommended.

An aside: In grad school, one of my colleagues was working on an occlusion study comparing the consistency of proper pressure applied among recreational lifters after feeling the clinician set the exact pressure needed. The study also compared between groups to see differences from wraps vs cuffs. In their opinion, without hunting the study down, I was informed that there was an overwhelming consistency among lifters who were able to accurately re-occlude themselves after a clinician showed them proper tightness. This means that I have full faith that the average lifter can benefit from the implementation of BFR training which is now backed by a body of literature.

There is a myriad of benefits that come along with BFR training. I’ll briefly touch on them and get straight to the implementation of this. When reducing blood flow by occlusion training should be done with extremely low load (around 30% of a 1 rep max). This in it of itself is the basis for its helpfulness and utility. BFR is primarily used in a clinical rehab setting while working to maintain strength and size of an injured limb. Without occlusion these low loads simply do not provide enough stimulus to yield any meaningful adaptation from the muscle. Occlusion paired with these low loads allow for the accumulation of metabolic damage cursers and slightly acidic pH (acutely post exercise) which have been shown to stimulate growth hormone (GH) release and muscle growth. BFR training allows for you to give your joints, tissues, and muscles a break from the heavy load training you should be implementing while still sustaining and maybe gaining some benefits* from the implementation of occluded training. BFR is something that shouldn’t always be in a program but can definitely supplement some phases where the athlete is either A. going through injury and can’t perform heavily loaded training or B. in the middle of some intense fatigue accumulation, maybe a little banged up, and needs to substitute in some BFR work as accessory work to take it easier on the joints. BFR can promote recovery in the arms and legs and can be great way to get some active recovery in. With all this talk about lower loads being lifted and this protocol or type of training being used for recovery one would think that BFR training would be something one could go through the motions but BFR training is not something to take lightly. The performance of BFR training is stressful and can be uncomfortable and is accompanied by an enormous “pump”.

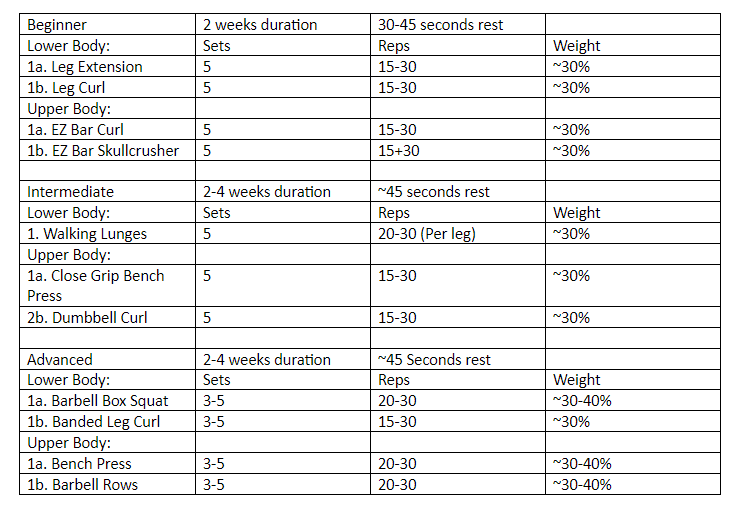

Now for the application of BFR Training. Generally because it is used so frequently with athletes who are coming back from injury they are in a tightly controlled environment that is usually restricted to the leg extension machine and the leg press. Assuming you’re not coming back from injury and don’t’ have to navigate the murky exercise selection waters that accompany that, you have multiple options available. There is nothing wrong with sticking to the leg extension or leg curl but you can be more adventurous with your selection. Starting out you want to do 3-5 working sets at around 30% to volitional failure. If you can accomplish over 30 reps easily, you’re not using a heavy enough load. If you’re doing upper body you should superset your biceps and triceps and for lower body your quads and hamstrings. The cuffs should be worn during the duration of the entirety of the BFR training part of the workout. Your rest should be around 30-45 seconds and no more than a minute. Personally, I would implement BFR for 2-4 weeks at a time.

Closing thoughts:

It’d be very interesting for me to see what kind of results one would get with pairing a BFR protocol with banded Terminal Knee Extensions (TKE) in a clinical setting, what the ramifications for the knee would be. The combination of proper tracking of the knee and stabilizing of the knee cap a la vastus medialis oblique (VMO) with the hypertrophic and strength wielding results of occluded training could be a on-two power punch for knee health and function. I am sure there are many other interesting exercise selections that BFR could be coupled with to make for some game changing results.